|

Reconstruction of the columned hall in the temple palace at Medinet Habu |

|

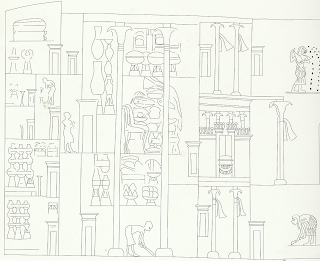

| Drawing of the bedroom and harim in Akhenaten's palace from the tomb of Ay at el-Amarna |

In reality, most palaces probably accommodated several of the above-listed functions just as some present day seats of government serve as residence for the head of state, chief administrative center and place for stately events. The ancient Egyptian king, moreover, had usually not just one but many palaces so that the royal power was represented in all the parts of the country, and at all places of royal interest. This included in the Old Kingdom, for instance, a palace at the site where the king’s pyramid was built. Each palace had a name. For instance a palace near the pyramid of King Djedkara lsesi was called “Lotus flower of Djed-kara. ” Considering the multi-faceted character of the royal palace, it is especially regrettable that relatively few remains of such buildings have been excavated. There is, moreover, an unfortunate chronological imbalance, since most palace remains date from the late 18th, 19th and 20th Dynasties. Even concerning the New Kingdom we only know through literary sources about the palace built by Thutmose I at Memphis in which such important pharaohs as Hatshepsut or Thutmose III must have resided. Under these circumstances, a general picture of royal palace architecture in ancient Egypt must be pieced together from scattered remains, and use must also be made of other than purely archaeological evidence. Representations of palaces in wall reliefs and paintings, for instance, are invaluable for a reconstruction of the visual appearance and uses of royal palaces; and there is an additional—very typically Egyptian—source from which basic insights about the structures of Egyptian royal palaces can be deduced. The late 18th and 19th-Dynasty mortuary temples in western Thebes are provided with full-scale three-dimensional representations of royal palaces.

|

| Plan of the administrative rooms in the great palace at el-Amarna |

These so-called “temple palaces” are always situated on the south side of the main temple with their axis at right angles to the temple axis. When first excavated, the temple palaces were believed to have served as rest-houses during visits of the ruling king to the mortuary temple. More recently, however, scholars have shown that most installations in these buildings were not suitable for actual use. The temple palaces are, therefore, now understood as purely symbolic dwellings For the deceased pharaoh in whose honor the mortuary temple was built. However, since the temple palaces appear to reproduce real life structures, they can well serve to demonstrate properties of now lost real palace architecture provided one keeps in mind the symbolic nature of this source.

|

Plan of the palace of Merenptah at Memphis |

Like all places of the living the kings residence was normally built of mudbrick with possibly some main doorways of stone. The walls, floors and ceilings were plastered and often painted, and columns and windows were of wood. More stone elements, such as columns and windows, were used in some temple and audience palaces as well as palaces for religious rites. The buildings had for the most part only one story with possibly some galleries as well as stairs to the roof. Furniture consisted of wooden (certainly often gilded and inlaid) chairs and beds with blankets and cushions‘ Gate-legged stands supported terra-cotta vessels and served as tables; and lighting was provided by oil lamps on pedestals. Foodstutt and goods such as linen clothing were stored in chests and on shelves supported on painted mud-brick walls‘ As best seen in relief representations showing the palaces of King Akhenaten at el-Amarna, the royal living quarters comprised an entrance portico, various columned halls and rooms with shrine shaped doors. In the center the representations depict a large columned hall whose ceiling is higher than that of the surrounding

rooms. This hall may have had clerestory windows just below the root. Here cushioned chairs and a sumptuous meal await king and queen. The main hall is in most representations preceded by a portico, or several porticoes, one of which contains an ornate window, the so-called “window of appearance," about which more will be presently said. Behind and at the side—of the large hall smaller rooms open to a narrow corridor. In the representations, most of the side rooms are filled with food supplies and boxes with goods.

In proximity to the kings bedroom some images from Amarna tombs depict columned chambers in which female musicians and dancers practice their art. In the corridors leading to these rooms men are seen standing, seated or talking to each other, while others prepare food and drink in adjacent rooms. It is tempting to interpret these representations as depictions of the kings harim. The presence in the abovementioned figure of foreign women with long curled tresses and “Syrian clothes” in their own separate room inside the musicians’ quarters could be taken to confirm such an interpretation, because it is known that a number of princesses from countries in Western Asia and the Levant became minor wives of the Egyptian king. However, during the last twenty years serious doubts have been raised concerning the existence in ancient Egypt of an institution comparable to the harim in medieval Turkish palaces. Scholars have stressed the fact, for instance, that the term kbener, often translated as “harim” actually identified a troop of dancers and musicians who performed at religious ceremonies. There appears to be no evidence that the members of this troop ever served in the role of royal concubines. In the light of this point of view the image would have to be interpreted as an indication by the Amarna artists that the pharaoh went to sleep accompanied by soothing music performed by beautiful women.

The kings bedroom has one of the ingenious roof constructions with which the ancient Egyptians managed to funnel the cool north wind into rooms . In one representation, the greenish-blue, dark brown and other dark colors in the faience tiles. No private apartments for king and royal family are, however, preserved from this period.

A number of bathrooms have been excavated. Like bathrooms in private mansions, they had a screen wall behind which a rectangular basin with a spout at one side is set into the floor.

Here the king could take a shower under water that a servant poured from a jar. A royal bathroom at Memphis was decorated with “protective hieroglyphs topped by royal cartouches and a cornice. Some representations in El-Amarna tombs

also show a pool in the residential compound with plants painted on the floor around it. King Akhenaten clearly preferred a river position (and river view) for his palaces. Both the large architectural complex that was most probably his major residential palace, the so-called “northern riverside palace,” and the “great palace” in the city appear to have had terraces overlooking the Nile. We will deal below with the pools and water vegetation in the palace at Malkata and the parkland sanctuaries connected with Amarna queens.

It is remarkable how close the general layout of the royal living quarters was to that of the elite houses at el-Amarna. Herbert Ricke has described this in his famous treatise Der Grundrzks ales Amama-W/obn/muses. Indeed, the front portico of the palace can be compared to the front rooms (broad halls) of the non-royal houses, while the palace’s high main hall finds its direct counterpart in the square main hall of the typical el-Amarna house. Bedrooms and other private spaces lie in both types of buildings at the side and back of the main hall and thus removed from the entrance. That the king and his family essentially lived in a grandiose version of a nobleman’s house makes sense. As far as physical needs were concerned every pharaoh was a human being, even if his special semi-divine qualities made privacy and seclusion a primary requisite.

1 Comments

Pharaohs did not have palaces as we understand them. These places where pharaohs stayed while they traveled through the country were made like everyone else's homes: of mud bricks. That is why they are not found. Egypt didn't have a real "capital," like DC, for example.

ReplyDelete