The accompanying illustrations are of objects in the Museum

of Fine Arts. All are of the Fourth Dynasty (2680-2560 B.C.) and fall into two

groups; first, portraits of private persons, high officials or princes, and

second, representations of kings and queens.

Figure 1 is the head of a prince whose name is not known.

It is rather conventional and represents a man of regular features

approximating to the Egyptian ideal of masculine beauty. While the face is

somewhat lacking in individuality, the head is one of the finest examples of

technical skill in handling soft white limestone of which the sculptors of the Old

Kingdom were capable.

Figure 2 is conceived in a very different spirit. It

represents a woman, wife of a prince of the royal house, and reveals the artist‘s

interest in a strongly individual head. The heavy skull and jaw, thick lips,

broad nostrils, and peculiar structural formation of cheek bones, brow, and

eyes contrast sharply with the regular features seen in Figure 1. It has often

been pointed out that this head shows strong negro characteristics, and it is

indeed quite possible that the woman represented was of mixed blood, possibly the daughter of an upper

Nilotic chieftain allied by marriage to the ruling house of Egypt. No concrete

evidence of this exists, however, and the question remains little more than an

interesting speculation In any case the head is no conventional type whether negro

or not - but a strongly individualized

representation of a particular person.

Figure 3 also carries conviction as a true portrait in the

modern sense. Somewhat summary in execution and finish, it betrays the hand of

a master working in broad planes and is instinct with personality.

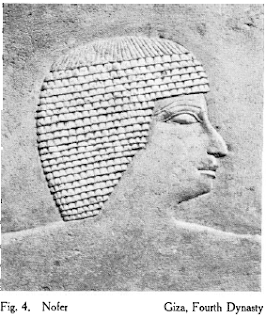

In the case

of this head we are fortunate in having a second portrait of the same person,

this time in relief (Figure 4). He was

an official of the highest rank in the financial affairs of the government, “Overseer

of the Two Houses of Silver,” Nofer by name. In the relief the eye is, of

course, rendered according to the universal Egyptian convention which sought to

avoid foreshortening in two-dimensional representation; but if one compares the

profiles in the head and in the relief one cannot fail to note the faithful

rendering in each of the aquiline nose, the peculiar formation of the upper

lip, and the contours of chin and throat.

The most convincing example of individualized portraiture

in the Pyramid Age is the painted limestone and plaster bust of Ankh-haef shown

in Figure 5 This unique masterpiece is remarkable for several reasons. The

subject was of the highest rank, had the largest tomb in the royal family

cemetery at Giza, and the inscriptions on it tell us that he was the “eldest

son of the king’s body” (probably Cheops, builder of the Great Pyramid), and

that he held the highest administrative offices in the kingdom, those of Vizier

and “Overseer of All Works of the King.” It is clear that he was an important

member of the immediate royal circle with the best sculptors of the court at his command. The

bust is exceptional both in form and material. It is neither a “reserve head”

nor was it ever part of a

complete statue, and we know of no other busts in the round like it. The technique

also is unusual, for the figure is carved out of fine white limestone and

completely covered with a layer of plaster of

Paris in which the finer modelling of the surfaces has been

executed. This was doubtless done while the plaster coating was still wet, and

the whole figure was then painted with the brick-red color normally used to

represent the flesh of men. This red color was even laid over the closely

cropped hair, a quite abnormal procedure, and only the eyes appear to have

been white with dark pupils. But what is most noteworthy noteworthy about this

unique head is its utter lack of convention and the startling realism of its

modelling. The magnificent shoulders, neck, and skull reflect keen observation

of nature and a thorough grasp of the structure beneath the surface. The

realistic rendering of the

rather small eyes is in marked contrast to normal Egyptian practice, and the

careful modelling of the face, the muscles round the mouth, and the pouches

under the eyes give evidence of minute observation of the living model. In the writer‘s

view the bust of Ankh-haef is the supreme example of realistic portraiture

which has survived from ancient Egypt, alike for its freedom from convention and

for its perfection of execution.

Source: DUNHAM Dows,

Portraiture in Ancient Egypt,

BMFA XLI, 68-72

0 Comments