Credit: Al-Majalla Magazine

For decades, Egypt has been a beacon of intellect and culture. Egypt’s newspapers, music, movies, television shows and literature mirrored Egypt’s cultural, economic and political stronghold in the Middle East and North Africa.

So important were the political narratives and developments coming out of Egypt that the country created its very own Foreign Press association in the 1970s which was meant to facilitate the professional requirements of foreign media correspondents. Fast-forward 40 years later, and the country, which was once a home to hundreds of foreign journalists reporting to international audiences, is quite possibly witnessing the lowest number of foreign media correspondents on its grounds.

Since 2011, Egypt has gone through a roller-coaster of events that have touched every single aspect of Egyptian life. One such aspect that is currently on its deathbed is Egypt’s fourth estate: the media.

The last standing state-owned and privately-controlled news media organisations have largely resorted to self-censorship, banning all material which “may incite” or otherwise undermine state institutions directly or indirectly – it is a “nationalistic duty” to tow the line.

While the years following the 2011 revolution saw significant media activity surrounding social, political, cultural and economic issues, there were already signs of weakening journalism on the horizon, with more and more journalists decrying harassment and pressure.

Nowadays, there is all but silence.

But why?

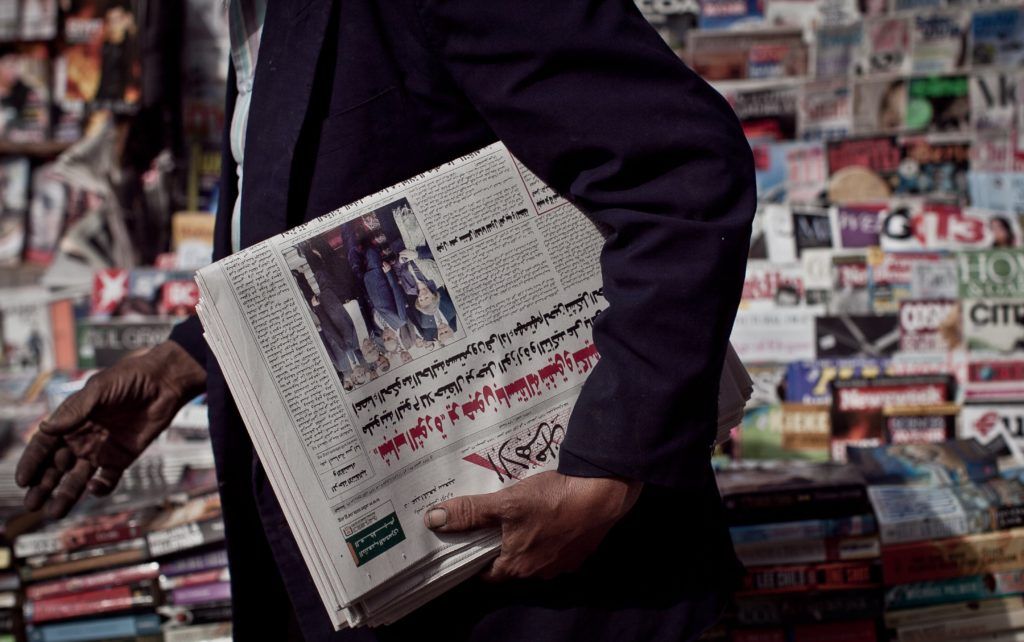

Egyptian reading a newspaper in Cairo in 2011 (Credit: Reuters)

Egypt has been facing significant pressures from both within and abroad that are aimed at undermining its development and stability. Egypt’s unique position in the region, along with its political, social and economic importance on a global stage, has seen the country become targeted by various state and non-state actors throughout its history.

While the number of terrorist attacks have certainly declined and the economy is showing strong potential and far greater stability, Egypt still needs to ensure it is able to continue on that path – if not for the sake of the current population, then for future generations to come.

To ensure that path, Egypt’s main mission became to not only convince foreign states that security and stability were crucial and thus justifying the ‘mean to the end’ but also its own population which, for the most part, suffered extensively from the 2011 revolution and would not be convinced to repeat any efforts at destabilizing the government at its own peril.

However, that path should not also result in the death of journalism – one that sees media organisations placing rose-coloured glasses on the eyes of its readers and audience. In fact, the destruction of the fourth estate threatens the very stability Egypt seeks to achieve.

For example, the lack of transparency and the growing self-censorship and press restrictions have resulted in a lack of confidence in which news outlets to trust, due to a fear of political bias, and an influx of informal information sources being relied on. Facebook, Twitter and even Instagram are the new community noticeboards: readers flock to them first for information about what’s happening in their communities. Then, readers try to piece news together through word of mouth, ‘official’ statements and, if possible, foreign coverage of local news.

While the form of ‘citizen journalism’ is important and has significant benefits (such as exposing underrepresented issues), there’s been an increase in the dangers posed by reliance on social media as the only source of information. Social media is unregulated and, as such, fake news and false information can spread like wildfire. Stories are sometimes even hijacked by those with ulterior motives maliciously seeking to cause divisions or incite violence and instability.

Worse yet, Egyptian media – even with its self-censorship to not be perceived as a source of fake news – is harming the government and the Egyptian state more than it is protecting it. Egyptian newspapers and talk show hosts are constantly ridiculed for their emotionally-charged, un-critical and redundant approaches to news and information: “Are activists demonstrating against the government? They’re terrorists. Are journalists publishing news revealing a serious social or economic issue that must be addressed? That’s just fake news meant to tarnish Egypt’s image before the world in order to kill its tourism.”

Recently, a number of Egyptian newspapers reported on prison conditions at the infamous Tora Prison in Cairo following a visit by officials. The coverage by Egyptian newspapers was unanimously and overwhelmingly positive, lacking any any critical (or simply unbiased) reporting: “Prisoners have barbecues, great access to facilities and have no complaints at all!”

As such, distrust in the Egyptian government and the ‘singular-voiced’ media flourishes and the image of Egypt and its government both locally and abroad is tarnished. Egyptian media is regarded as window dressing – and not even the pretty kind. When an important story does come around – one that would benefit Egypt – people, especially foreigners, are hesitant to trust the media: “Is Egypt’s economy really improving or is this just another embellishment by Egyptian newspapers? Are tourists really returning in troves? Is Egypt really safe? Or is Egypt so keen on improving its current state that it repeats the same positive mantra over and over again until it hopefully becomes a reality?”

In addition to this, without reliable, critical sources of information, even Egyptian government leaders and representatives are shrouded in darkness: if no one is reporting on an issue, how will they know it exists so that it may be addressed in a country of 100 million people?

More than five million Egyptians work for the government sector. Lacking the checks and balances the media provides through uncovering and reporting on issues, those in managerial or leadership positions struggle to ensure effective and efficient tackling of key economic, social and cultural issues.

These issues are worsened by a lack of transparency. The Egyptian government does not hold regular press conferences and official data, such as statistical reports, is not designed to be accessed, processed and read by non-governmental individuals, for the most part.

A protester at the Press Syndicate in Cairo in 2016 (Credit: Reuters/Mohamed Abd El Ghany)

There is little flow of information from Egyptian government departments – particularly from the security apparatus. In some cases, Egyptian government departments ignore stories and information that have been widely reported on social media for days, and sometimes even weeks, before a statement is released. For particularly ‘sensitive’ and ‘politicised’ stories, local media doesn’t dare publish a single report until the Egyptian government has spoken.

That means for hours, days or weeks, people having nothing to rely on other than what is published on social media or in foreign press. Apart from misinformation, this deprives Egypt of a voice in the media sphere: people, especially foreigners, consuming news about Egypt will almost always get it from foreign sources.

The influx of misinformation on social media coupled with a biased, disengaged Egyptian media landscape, leaves us with a bubbling volcano on the verge of eruption. When a major incident occurs – or when a highly politicised story is reported on by foreign media or on Facebook – people do not have a source of information they can rely on. Such misinformation can be easily weaponized.

More importantly, Egypt is being robbed of its voice and of its position as a role model – a beacon – for the Middle East and North Africa.

So what’s the solution?

It is important not to glamorize the past. In the years both post- and pre-2011, Egyptian media was rampant with exaggerations, fabrications and infringements which breached the most basic journalistic ethics. Media organizations and popular journalists were often more concerned with upholding the demands of their corporate overlords at the expense of the people and country.

The Egyptian Parliament should take the first active steps to allow for the revival of journalism in Egypt. This includes by imposing new laws which are aimed at protecting the media as a vital component of the Egyptian State, one which the State cannot operate without. Journalists should have the necessary protections to report with integrity on the issues that impact everyday Egyptians.

No journalist should be afraid of reporting a story, as long as such reporting is accurate, factual, verifiable and done with integrity. A journalist’s duty is to serve the people: not the government, corporate entities, or their own personal interests. The Egyptian Parliament should ensure this duty is upheld, protected, and allowed to thrive.

The Egyptian Parliament should also urge greater transparency and flow of information from all government departments: it should no longer take hours or days before a government department or spokesperson responds to a major incident related to that department.

Regular press conferences to openly answer queries from journalists – both local and foreign – would undoubtedly tackle misinformation while providing the public with information they deserve to know. Egypt needs to regain its voice, and one simple way of doing so is by increasing transparency rather than allowing its population to suffer from ignorance.

The transparency would also allow the Egyptian government to form stronger ties with independent media organizations. With Egypt still vulnerable to external and internal threats, it is important for the Egyptian government to more actively communicate with journalists and media organizations to ensure the accurate flow of information.

A protester holds up his hands, which are chained together, during a protest in front of the Press Syndicate in Cairo 10 June 2015 (Credit: Reuters)

A new media framework is also necessary, one that governs how media organizations and journalists engage with society and carry out their duties. This cannot be done by simply rolling back self-censorship and restrictions.

An overarching and transparent media framework, one that includes a clear code of ethics that holds journalists accountable to high journalistic ethics and integrity, is paramount. Journalists must be held accountable for breaches of such ethics: we should never again see an article published by a popular Egyptian newspaper claiming ‘the Muslim Brotherhood, Jews and Shias are the three evils of this world‘.

Journalists in Egypt need to do better. Media organizations must be fully committed to the basic principles of journalistic ethics. At the same time, there needs to be a space for local journalism to thrive.

In a new media framework, journalists should not be punished for simply reporting on news that is difficult to swallow. Journalism with integrity should never be silenced, even more so in states that are in dire need of change

A strong media framework that protects the media’s core role as the fourth estate will strengthen the groundwork for real, effective and inspirational change. The first step is by recognizing the power of journalism to be a positive driver of change, to address the harsh realities the media has remained silent towards and to give Egypt back its voice.

* This article was originally published here

0 Comments